Noh Oshima Bulletin

The cover stories of our bulletins published twice a year.

№30 cover story (2014/09/20)

One Hundred, and Another, Still Another

OSHIMA Masanobu

We would like to thank all the audience who came to the Memorial Noh Performance for the 100th Establishment Anniversary of Oshima Noh Stage. Also we are grateful to have received the Chugoku Culture Award (the Chugoku Newspaper) and the Saika Award (Noh Theatre Research Institute of Hosei University). We do recognize that these honors are given by the help of every one of the supporters.

A young man from Taiwan staying at a school of the Japanese language, who happened to find us on the Internet, came to Oshima Noh-gaku Do this summer in order to learn about the Noh-gaku. He visited us four times, learned a little about Utai and Mai, and performed a little on the stage with Montsuki and Hakama on. Not enough, of course, but he was so pleased as to say that he comes here again to practice more.

Fukuyama City was formed as municipality in 1917, when my grandfather Oshima Jutaro produced and performed the Noh piece "Tomo-no-ura." The city is planning several big evens for the hundredth anniversary in 2016, so we would like to join the events because he must have produced his piece to celebrate the birth of our city. This time, we are thinking of producing a brand new Noh piece, where Mizuno Katsunari and Abe Masahiro appear on the same stage. Katsunari, a cousin of Tokugawa Ieyasu, became the first lord of Fukuyama Clan in the early 1600's; and Masahiro, also the lord of Fukuyama Clan but in the middle of 1800's, was one of the supreme statesmen at the end of Edo Era, who led Japan to open to the world peacefully. They meet each other on the stage over time and space and talk about the city. We hope you would like this coming new Noh piece.

№29 cover story (2014/04/15)

The Effectiveness of the Noh Practice

OSHIMA Kinue

I'm sometimes surprised to be asked "Are we the ordinary people allowed to practice Noh?" The performances with Noh masks or gorgeous costumes would make them hesitate to begin the practice.

The Noh tradition of six hundred years has been kept up not only by the experts but also by the warriors in the Sengoku Era, the citizens and their children in Edo Era. They all practiced Utai and performed Mai to develop themselves. And nowadays the Utai "Takasago" is recited at the wedding ceremony, some others on happy occasions, which I think shows a bit how the tradition of Noh-gaku has been inherited.

By practicing Utai, your breathing becomes deeper; by practicing Mai, you can promote your ability of concentration and get the straight core in your body which keeps you in a good posture; and also your 'inner muscles' will be built up. It is said that the body and mind of the Japanese people are recently becoming fragile with a shallow breathing and poor inner muscles in the convenient life style. The practicing of Utai and Mai is surely effective.

There is a saying "Utai has ten virtues, fifteen virtues," that is, "You can appreciate the sights without visiting them," or "You get acquainted with the origin and history of things without their experiences." In practicing Yokyoku (the words of Utai), which describe old stories, myths, or legends of some area, you sometimes have a sense of seeing various sights and touching the wisdom of the ancients. That must be an effect acquired along with practicing Utai.

In Japan we have several arts attached with the word "-do (way)": Sado (tea ceremony), Kado (flower arrangement), Shodo (calligraphy) and so on. People learn, practice and study the art, considering it as a way of their life. People hold the art as a kind of principle rooted in their mind. Being a part of the Japanese culture, though without the suffix, Noh-gaku is in our everyday life and subsists in our culture as ever.

Jubilith’s Noh Costume Workshop Report for Mrs. Oshima!

Jubilith MOORE

〈Summary〉

The Theatre Nohgaku Noh Costume Workshop was a unique opportunity to learn about the rich use of costuming in Noh, one of the world's most refined art forms. We considered how costumes are made, how they are selected for performance, how they are cared for, and the exquisite choreography of being dressed. Divided into two distinct sections, the first, led by Kyoto based Monica Bethe, who has an unrivaled knowledge of Noh costumes, was delightfully, and surprisingly, hands-on. The deeply informative daily lectures were broken up with field trips to actual artisans in such areas as weaving, embroidery and gold stenciling, continuing the ancient traditions. Kita Noh Shitekata Oshima Terahisa masterfully led the second part of the workshop, again providing thoughtful hands-on instruction. Provided with an introduction to the masks and costumes for an ensuing performance we then had the extraordinarily rare and wonderful experience of witnessing a rehearsal. Following the actual performance, we spent two days practicing Noh dressing for various women and men's roles (e.g. angels, mad women and demons). We also practiced putting on a basic woman's wig, learned the principles for costume folding, the importance of thread and some basics of costume maintenance.

The Theatre Nohgaku Noh Costume Workshop was a unique opportunity to learn about the rich use of costuming in Noh, one of the world's most refined art forms. We considered how costumes are made, how they are selected for performance, how they are cared for, and the exquisite choreography of being dressed. Divided into two distinct sections, the first, led by Kyoto based Monica Bethe, who has an unrivaled knowledge of Noh costumes, was delightfully, and surprisingly, hands-on. The deeply informative daily lectures were broken up with field trips to actual artisans in such areas as weaving, embroidery and gold stenciling, continuing the ancient traditions. Kita Noh Shitekata Oshima Terahisa masterfully led the second part of the workshop, again providing thoughtful hands-on instruction. Provided with an introduction to the masks and costumes for an ensuing performance we then had the extraordinarily rare and wonderful experience of witnessing a rehearsal. Following the actual performance, we spent two days practicing Noh dressing for various women and men's roles (e.g. angels, mad women and demons). We also practiced putting on a basic woman's wig, learned the principles for costume folding, the importance of thread and some basics of costume maintenance.

Something I am happy to now possess is a new way of seeing. Prior to this workshop, my experience of Noh costumes (and perhaps costumes in general) was simply to be astonished by their overwhelming and exquisite beauty. Now, when I look at a costume, I am intimate with its parts, have a basic understanding of how it was conceived, from thread to completion, as well as how it was put on. I also have a new appreciation of how (Noh) costumes work to create the visual statement of the production.

〈Impact〉

The impact of my participation in the Noh Costuming Workshop on Theatre of Yugen will be significant and long-term, creating a Company 'before' and 'after' workshop. I see this unfolding in two direct ways; first, in terms of the maintenance, preservation and wearing of the costumes and second in relation to the costume design of our traditional repertoire as well as our adaptations and new works.

With a Kyogen in English repertoire active since the Company's inception in 1978, and with costumes that have nearly made that entire journey, many are in need of serious repair while many have laid dormant for some time. Without the significant resources to replace, and thus permanently retire these long standing dormant pieces, it would be ideal if we could extend their performance lives. This would be a service to their heritage as well as to the performers and our audiences. In addition to our costume collection, we were recently gifted with a valuable costume collection that came to us in good shape. It was my eagerness to not see this costume collection go the way of our current holdings that prompted me to seek out this Costume Workshop.

Now possessed of this workshop experience and a very basic knowledge of some maintenance techniques, my former combination of ignorance and reverence has been suspended. Formerly restrained from caring for our costumes, particularly the older, finer ones, I now at least have some idea of where to begin, and am eager to expand my knowledge through research and hands-on experience. I also wish to indoctrinate my colleagues and community with a 'reverent but fearless' way of working with traditional costumes.

Previously I costumed our repertoire based on what had been done before and what costumes were in performance worthy condition. With some understanding of the traditional guiding principles of costume selection and a real appreciation that costumes are worn for their impact, not because it is tradition, I look forward to how my love of these costumes will find its way into all my work.

〈Conclusion〉

I began the workshop exhausted, resentful, burnt out and frustrated. Following the workshop, I have renewed faith in the utility of art and beauty and am beginning the slow delicate work of reinvigorating my artistic practice, which gratefully I have been reminded is the most important aspect of my life. The fight to be able to engage in my artistic practice had become a more engrossing battle and I'd gotten lost in the reality of life played out in the immediacy of now. The opportunity to meet, watch, listen to and study under traditional artists who, unfortunately, must fight the same battles as myself, was profound. Their ability to generously, even joyously, fight these battles in community and in full knowledge of their futility was a powerful reminder that life's value is found not in the end goal, but in the journey. In the end, art may not win the day, but that should not deter me, as it has, from giving my life to an artistic practice that actually makes it worth living.

I began the workshop exhausted, resentful, burnt out and frustrated. Following the workshop, I have renewed faith in the utility of art and beauty and am beginning the slow delicate work of reinvigorating my artistic practice, which gratefully I have been reminded is the most important aspect of my life. The fight to be able to engage in my artistic practice had become a more engrossing battle and I'd gotten lost in the reality of life played out in the immediacy of now. The opportunity to meet, watch, listen to and study under traditional artists who, unfortunately, must fight the same battles as myself, was profound. Their ability to generously, even joyously, fight these battles in community and in full knowledge of their futility was a powerful reminder that life's value is found not in the end goal, but in the journey. In the end, art may not win the day, but that should not deter me, as it has, from giving my life to an artistic practice that actually makes it worth living.

Jubilith MOORE

A graduate of Bard College and a Founding Company Member of Theatre Nohgaku, Jubilith Moore is the Artistic Director of Theatre of Yugen and has been a student of Yuriko Doi, since 1993. She acts, directs and writes for the theatre and has devoted her professional life to exploring the ongoing life of traditional Japanese and contemporary American theatre. She has studied Noh with Richard Emmert, Akira Matsui and Kinue Oshima (Kita school). While under a Japan Foundation Fellowship in Tokyo, she had the honor of studying with Kanze School Noh master Shiro Nomura, Kyogen master Yukio Ishida (Izumi school) and Kotsuzumi Noh drum with Mitsuo Kama (Ko school). Noteworthy roles are the Old Man in the At the Hawk's Well National Tour 2002, the Waki role in Greg Giovanni's Pine Barrens; She led the chorus for David Crandall's Crazy Jane and performed the role of the Waki in Jannette Cheong's Pagoda, an English language Noh performed to critical acclaim in a European tour (2009) and an Asian tour (2011).

№28 cover story (2013/09/15)

Grandpa's Memo, a Stone Bridge to my Master

OSHIMA Teruhisa

Nineteen years have passed since I came to Tokyo at the age of eighteen in order to get practice in earnest, which has made my stay here longer than the time in Fukuyama where I was born. While I was in my hometown, I did practice but that was just what my grandpa, the third Hisami, told me to do, as I was not an enthusiastic student then. An idea that I should ask him anything about the practice had not occurred to me, for Noh-gaku was just what he did.

In August this year I had a chance to perform "Raiden --- kae-shozoku" in the Takigi-noh at Sanwa-no-mori Koshinji Temple. The title has a 'kogaki (= kae-shozoku)' meaning "a special direction," and the performer has to play somewhat extraordinarily. I gradually came to think it hard to deal with.

In August this year I had a chance to perform "Raiden --- kae-shozoku" in the Takigi-noh at Sanwa-no-mori Koshinji Temple. The title has a 'kogaki (= kae-shozoku)' meaning "a special direction," and the performer has to play somewhat extraordinarily. I gradually came to think it hard to deal with.

Then, remembering that my grandpa was a diligent writer, I looked for his memos he wrote when I went back home. Yes, there was! He had taken notes of his thinking about "kae-shozoku," he had also wondered how to perform this piece. Nineteen years after I left home, I was able to feel my grandpa at last and my heart leaped up.

In the one-hundred-year course of our Oshima Nogaku-do Stage, I only carried out about twenty years. My predecessors must have passed several kinds of difficulties, which I am proud of and thankful for. And at the same time, I do have to take my responsibility to succeed to the tradition.

In the event of the Memorial Noh Performance for the 100th Establishment Anniversary of Oshima Noh Stage, I will perform "Ishibashi (Stone Bridge) --- renjishi" under the coaching of Mr SHIOZU Tetsuo, who has been my master since I came to Tokyo for the first time. Though this piece had long ceased to be performed, Kita Shichidayu, Kita-ryu the first, had it revive. So, this piece is a special one for our Kita-ryu. While most pieces of Noh are full of gentle movements, this shows one of the Noh different summits because of 'Shishi' which includes the hardest 'mai.' "The beauty beyond the strength" is what my master is pursuing for his life, and it is my aim too. I do ask for your support as ever.

A Gift from My Grandfather

Nancy H. Ross

On account of my grandfather, there has never been a time in my life when I was not interested in Japan. William A. Ross came to Japan in 1947 as a civil servant employed by the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (GHQ). He evidently fell in love with Japan because he returned home with all sorts of Japanese things: dolls, china, lacquerware, scrolls, just to name a few. I became accustomed to seeing those things from a very young age and was fascinated by their beauty and exoticism. My interest has never waned.

My grandfather died when I was 17 after years of declining health as a result of Parkinson's disease. Thinking back, I regret that I didn't ask him about his life in Japan. The little information I have now is based on a few documents that were passed on to me by my father. But because of my grandfather's influence, I regularly sought out opportunities to be exposed to Japanese culture. Living in Los Angeles and New York, where there are many Japanese and Japanese-Americans, I had opportunities to go to exhibitions of Japanese art and to see various performances and films when I was young.

In the back of my mind, I always had the idea of visiting Japan someday, but I never managed to get around to it. Then one day someone suggested that, in light of my keen interest in Japan, perhaps I should consider getting a job and living there for a while. That inspired me, and in 1993 I came to Fukuyama as an English instructor.

I immediately began to try to learn more about the traditional culture that I was so attracted to. I had seen performances of bunraku puppet theater and kabuki in the United States, but I first saw Noh in the summer of 1993 at an outdoor performance at the Hachimangu Shrine in Fukuyama. I don't recall what play was performed nor can I honestly say that I fell in love with Noh that night, but I went to see several more performances without really understanding them.

I immediately began to try to learn more about the traditional culture that I was so attracted to. I had seen performances of bunraku puppet theater and kabuki in the United States, but I first saw Noh in the summer of 1993 at an outdoor performance at the Hachimangu Shrine in Fukuyama. I don't recall what play was performed nor can I honestly say that I fell in love with Noh that night, but I went to see several more performances without really understanding them.

I have played the flute since I was 10 years old, so a number of years ago when a shinobue flute class was opened at the Fukuyama YMCA, I signed up immediately. Then one day in the spring of 2006 a member of the class passed out a flier about nohkan (Noh flute) lessons that were going to be offered, and I began taking lessons from Shuhei Yagihara. That was when I first went to the Oshima Nohgakudo.

Having played the shinobue, I had no trouble producing sound on the nohkan, but I had only a vague knowledge of Noh and little grasp of the role of the musicians. Under Yagihara-sensei's careful tutelage, I gradually expanded my knowledge and learned to play the various dances. I'm now preparing for a recital in October.

Since my childhood I have been interested in percussion also and have taken some wadaiko (festival drumming) lessons. On several occasions I had the opportunity to see Norie Oshima's impressive performances on the taiko and wished I could study with her. Luckily, she began offering lessons, and in January 2010 I started studying taiko with her.

We began with the onori (a form of congruent rhythm) parts of Oimatsu, Kakitsubata and other plays, which meant that I had to coordinate my drumming with the chant. Norie-sensei gave me copies from the utaibon (libretto), which I had never seen before, and together we sang the onori part. This little bit of utai (chant) practice was so enjoyable that after a while I asked Norie-sensei to teach me utai also. Now, while bombarding her with questions, I enjoy studying both taiko and utai.

I love utai because I can learn about language, history, religion and literature. It is relaxing as well. At the spring recital in May of this year I had my first opportunity to join the chorus of a Noh play when Norie-sensei played the shite (lead actor) in a performance of Tamakazura. It was very exciting.

Unfortunately, I can't help but stick out whenever I appear on stage, and for that reason I sometimes feel extra pressure. On the other hand, that pressure motivates me to try harder so I won't make mistakes when performing in front of people.

Now that I'm fascinated by Noh, my only regret is that I didn't start studying it when I was younger, but I plan to continue taking lessons from now on. I'm sure my grandfather would be pleased.

Nancy H. Ross

Graduate of the University of California, Riverside. Came to Japan in 1993 after working in various jobs including newspaper reporter, editor and public relations officer. Works as a translator and editor and also teaches translation at the Fukuyama YMCA. Winner of the Distinguished Translation Award in the 4th Shizuoka International Translation Competition and the First Kurodahan Press Translation Prize. Resident of Fukuyama. Cat lover.

№27 cover story (2013/04/15)

The 100th Establishment Anniversary of the Oshima Noh Stage

OSHIMA Masanobu

A hundred years have passed since the old Oshima Noh Stage was established at Shin-baba-cho (now Kasumi-cho). The stage there had a 3-gen square stage with the hashigakari of 5-ken and the kagami-no-ma of 2-ken, which was really a full-scale Noh stage in a rural area (-gen, -ken is a bygone unit of length; 1 ken is about 1.8 m). The Second Hisataro (at the age of 44) put his blood and realized the dream of the First Shichitaro. Hisataro wrote in his diary about his fatigues to scrape up enough money, though some of his pupils and sponsors properly helped him one way or another.

In April of 1914 a large number of guests, including the 14th Rokuheita and Mr KANEKO Kamegoro, assembled and the opening ceremony was held. That was also the beginning of Noh Oshima Family. Unfortunately that Noh stage was burned down because of the war flames. And the present Noh stage was built in 1971 by my father, the third Hisami. It was unusual in those days to place a Noh stage inside the reinforced concrete building, and with chairs at the auditorium.

In April of 1914 a large number of guests, including the 14th Rokuheita and Mr KANEKO Kamegoro, assembled and the opening ceremony was held. That was also the beginning of Noh Oshima Family. Unfortunately that Noh stage was burned down because of the war flames. And the present Noh stage was built in 1971 by my father, the third Hisami. It was unusual in those days to place a Noh stage inside the reinforced concrete building, and with chairs at the auditorium.

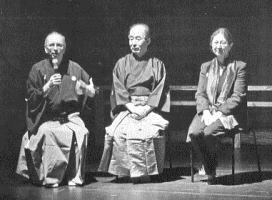

This December, We are going to carry out a commemoration Noh performance, turning our thoughts toward our seniors and the days gone by. I am going to perform a secret piece "Tokusa" with my grandson Iori, and I hope to express the profound regard of the old father for his child.

My son Teruhisa, now practicing diligently under the discipleship of Mr Shiozu, will be allowed to perform Shishi on this occasion and to perform ren-jishi with his master.

In the book of Zeami, it is said, "The family becomes a family when it is succeeded from one to another; the man becomes a man when people recognize him." As one Noh-gaku performer, I do wish that my son and grandson firmly carry on this family traditions.

And, I sincerely do ask everyone to support us as strongly as ever. Thank you very much.

№26 cover story (2012/09/15)

To Teach and to Learn

OSHIMA Kinue

At a college I was again in charge of the subject "Japanese Music" for the teachers who renew their teaching certificates. It is one-day course of six hours and this year I worked on building up the program in order for them to apply it to their daily lessons.

In many of their reports this year they say that they will adopt the way of raising the voice because they have noticed how wonderful it is. I hear they have little budget to buy Japanese musical instruments, or even if they have, they cannot teach their students how to play them. Then, I thought, with their own body I will let my teacher-students experience utai, the basis of Noh, from which they can go farther into the Japanese music or our traditional art. I feel happy to find the reports say they start their way.

In many of their reports this year they say that they will adopt the way of raising the voice because they have noticed how wonderful it is. I hear they have little budget to buy Japanese musical instruments, or even if they have, they cannot teach their students how to play them. Then, I thought, with their own body I will let my teacher-students experience utai, the basis of Noh, from which they can go farther into the Japanese music or our traditional art. I feel happy to find the reports say they start their way.

The refreshness of speaking out and the pleasantness of "uta (singing)" are seen everywhere around the world. By reviewing the Japanese way of uttering, which suits the body of the Japanese people, we can overcome the weakness of our mind and body. This suggestion is by Ms YAMAMURA Yoko, a Nogaku-shi of Kanze School. I am deeply impressed with her theory, and get a lot of ideas from her speeches and books.

On the event "Kokoromi no Kai" presided by her this spring, I performed the shite of 'Semi-maru'. And I was able to learn a lot in the course of practicing and tense stage with women Nohgaku performers of a different school. I am grateful to be on that stage, thanks to Mr TOMOEDA Akiyo of Kita School, and other honorable masters of Kita and Kanze Schools, supporting staff, and above all, Ms YAMAMURA Yoko.

№25 cover story (2012/04/15)

The most important thing about Noh

OSHIMA Teruhisa

I would say it is Noh-men (the masks).

Noh-gaku performers carry their masks with them wherever they go, in a very tough bag called 'Men-Kaban'. That is because we have an inmost thought for the mask, not just as a tool. The Japanese word noh-men is sometimes used as a comparison to 'a face without any feelings', but this metaphor is a glaring error.

We have at our house a noh-men named "Manpi", which my late grandfather thought highly of saying this is the most precious treasure in my family. It is used when we perform as a role of a young woman. This mask appears glamorous as well as adorable. The amplitude of its expression amazes me every time I see it. Besides my heart pulses with the impression of its endless possibility.

Wearing a noh-men makes our sight very narrow. Just as it is very hard to stand straight when you close your eyes, being narrow-sighted with a noh-men has a big influence on your sense of balance. You must gather a lot of practices and experiences in order to move naturally wearing a noh-men. Suriashi and kamae, which appear to be unique, may be developed in a situation of performing with a noh-men.

When I was a junior-high student, I wore a noh-men for the first time of my life. Even now I realize that complete darkness, and I almost shouted. When I perform with a noh-men on, I feel I am in another space though I am at the center of the stage, because of the darkness. As I keep on performing, my body becomes tired, but in reverse my soul becomes calm and I am looking at myself calmly, then I feel satisfaction beyond description.

Noh masks make a shite play various roles, also internally they have an incredible effect on the performer. That is why I think them the most important item about Noh.

№24 cover story (2011/09/15)

The "Pagoda" Asian Tour

OSHIMA Masanobu

I would like to express my gratitude to every one of you for supporting the tour.

I would like to express my gratitude to every one of you for supporting the tour.

The performance of the new Noh piece "Pagoda" in English was held at the National Noh-gaku Do in Sendagaya, Tokyo, on June 28, which was the beginning of the tour this time going from Tokyo to Kyoto, to Beijing and Hong Kong in China. In the dressing room, where we have only Japanese people because it is the central theater of Noh-gaku performing, more than ten American performers stroll around with Japanese traditional dress 'Montsuki' on.

Prior to the stage of "Pagoda" in Tokyo, I had played the shite role in Noh "Takasago," and I watched it from the backstage. At the "Pagoda" European tour two years ago, the Noh piece was performed only on the stage of the theaters for operas or dramas. This time, for the first time, they performed it at the typical Japanese Noh stage, where 'Hashigakari' is at the left side for the performers to enter and exit, and the shape of the stage is a three-'gen' square (a 'gen' is about 1.8 meters long). I found this style of the stage much more effective in order to feel that the players and the audience are all the participants in performing Noh.

As the chief supervisor, I was so apprehensive for the evaluation of our English Noh performance at the National Noh-gaku Do, to be honest. Don't they consider the pagoda setting strange to the traditional stage? Well, they made it! All went well, and I was relieved to see that the audience approved of the performance.

A big project like this is very hard to realize. The enthusiasm of Ms Jannette Cheong and Mr Richard Emmert has led us all the way; The support and aid by the Culture Agency of Japan and all the vigorous sponsors has helped us. I am grateful to all of you for the successful tour of the "Pagoda" Asian tour.

№23 cover story (2011/04/15)

Filled with Respect

OSHIMA Kinue

"How 'modern' Noh is! I was astonished, when I first watched it."

I had an opportunity to talk with Mr IKEDA Takekuni, who is a pioneer of building the Japanese skyscrapers. He has devoted his energies to the reconstruction of Postwar Japan from the very beginning. To his house with a thatched roof standing at a cape in Nagasaki, I was allowed to go, being introduced to him by Mr Fujimoto, a chief priest of a Shinto shrine.

"I met with Noh when I was thinking of constructing a high-rise building with as little waste as possible. I was really astonished to find out that the Japanese tradition has done with it since several hundred years ago!" From a void it begins, into a void it ends. This is an ordinary way of the art, which Mr IKEDA calls 'modern.'

Huis ten Bosch (Hausu tenbosu), which he designed, has a circulation system concerning electricity and water. He aimed to build a future city within which things are produced and consumed. But, "A good example is found in a town of the Edo era," he said. How important it is to recognize a real way of the Japanese life, living with Nature and cherishing a sense of respect for Nature. "The human being is lived by Nature. We must not forget the mind of being respectful for Nature." The answer to a more and more 'modern' construction lies in the tradition of Japan.

We might have been seeking for desire. Now is the time coming when the Japanese people have to start all over studying the mind of their tradition including Noh-gaku, to make their future better.

№22 cover story (2010/09/15)

OSHIMA HISAMI, the 7th Anniversary of his Passing

OSHIMA Teruhisa

I am going to perform "Dojoji" in "the OSHIMA HISAMI Memorial Noh Performance." My grandfather, Hisami, was so healthy that I had never imagined that I would offer my "Dojoji" to his 7th anniversary.

"Keep practicing many and many times, then what seems meaningless becomes meaningful." This is the most impressive word I acquired from my grandfather. Sixteen years ago, just before I went up to Tokyo in order to get earnest training, he began uttering some talks on Noh-gaku. At that time I was not aware enough. But, gradually I came to understand what he meant.

"Dojoji" is a special piece for Noh performers. It is sometimes thought to be a graduation exam of the apprentice period. It has several highlights, one of which is 'Ran-byoshi,' a single combat with Ko-tsuzumi which last more than thirty minutes; its dance is an only movement of the tiptoes led by the strong and keen calls. This is just what my grandfather said: from naught to entity. The energy accumulated during the Ran-byoshi blows out at a burst in 'Kyu-no-mai.' It is followed by the desperate 'Kane-iri.' "Dojoji" is an extraordinary piece in every sense.

The pleasure to perform such a great work, the gratitude to all the people who have supported me until today. And the inmost thought to my grandfather, who led me to this art. With these, I would like to perform "Dojoji" on October 31.

The Legacy of Our Forebears

OSHIMA Yasuko

"If I'm lucky, I would like to carry out my father's wishes and pass nōgaku down to posterity."

This is something Hisatar? Oshima wrote in an old notebook in which, in fine brushstrokes, he neatly recorded facts about the ancestors of the Oshima family and kept a record of Noh performances and practices. Reading between the closely written lines, one can sense Hisatarō's passion for Noh and his love for his family. This notebook, which my father-in-law Hisami showed me soon after I married into the Oshima family, is a family treasure.

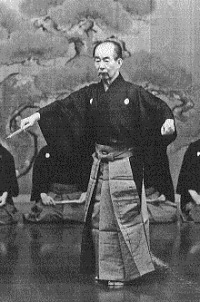

Born in 1871, Hisatarō Oshima was introduced to nōgaku at a young age by his father Shichitarō. While employed as a teacher, Hisatarō went to Tokyo during his long vacations for Noh training with the head of the Kita school and worked to popularize nōgaku. But at the earnest request of Roppeita Kita, 14th head of the Kita school, in 1911 Hisatarō reluctantly resigned his post as the first principal of Jutoku Elementary School and dedicated his life to Noh.

Believing that just as a samurai has a castle, a Noh performer needs a Noh stage, in 1914 Hisatarō rented land near Fukuyama Station, north of his residence on the site of the current nōgakudō. There he built a Noh stage and set to work to popularize Noh. Because he had eight children - four boys and four girls - life was evidently quite difficult after he quit his steady job as a teacher. But he procured the costumes and other items necessary to put on performances, and crisscrossed the country in an effort to promote Noh. His records indicate that he traveled to Kagoshima, Tokushima, Osaka and Sendai.

In 1917 Hisatarō wrote the Noh play Tomo no Ura, which had as its subject the local area of the same name, and appeared as shite. In 1920 he invited Roppeita Kita to appear in a performance of Dōjōji on the Oshima Noh stage. In his notebook he wrote, "Audience: 500-600. An unprecedented success. Expenses: 2,177 yen."

In 1917 Hisatarō wrote the Noh play Tomo no Ura, which had as its subject the local area of the same name, and appeared as shite. In 1920 he invited Roppeita Kita to appear in a performance of Dōjōji on the Oshima Noh stage. In his notebook he wrote, "Audience: 500-600. An unprecedented success. Expenses: 2,177 yen."

In 1925 a performance of Mochizuki was presented to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Sōemon Haneda. Other performances that year were Ama with Masayasu Umezu as shite and Kagekiyo with Roppeita Kita as shite and Senroku Ito as tsure. Mochizuki featured Hisatarō as shite and Hisami as kokata.

In his notebook Hisatarō recorded the sad fact of the death of his eldest daughter Kimie, who had moved to Seoul after marrying and who died on June 17, 1926, at the age of 22 while giving birth to her first child. The journal closes with an entry noting that Emperor Taishō died at 1:25 a.m. on December 25 and that the Shōwa era had begun.

In 1927 Hisatarō appeared as the shite in Shōzon, and in 1928 a special performance was held to commemorate the 17th anniversary of the death of Shichitarō. In May 1929 Hisatarō was the shite in a performance of Hyakuman that was staged in Kure.

But on September 21 of that year Hisatarō died at the age of 59 without fulfilling his life's ambition. At that time his eldest son Atsutami (Masanobu Oshima's real father) was a college student, his third son Hisami was in junior high school and his youngest child Sachie was 7 years old, so Hisatarō's wife was at a loss. It is said that she sold the fields near their house to get money for living and school expenses.

After graduating from college Atsutami became a teacher, while Hisami was apprenticed to Roppeita Kita upon graduating from Seishikan Junior High School. Thus three generations of the Oshima family - Shichitarō, Hisatarō and Hisami - studied under Roppeita. Soon after the war Hisami began extending frequent invitations to Roppeita to appear in performances, and the family photo album has rare photos of him enjoying fishing in the sea at Tomo no Ura and Onomichi.

In 1949 Hisami built a Noh stage at the current location, and in 1958 he began to hold regular performances (nōgaku classes) four or five times a year. In 1971 he erected a three-story reinforced concrete building housing a Noh theater, and many grand plays as well as hikyoku, secret pieces forbidden to those not formally certified, were performed.

During a televised interview Hisami once said, "The Noh stage that had been at my home ever since I was born burned down in the air raid on Fukuyama, and I felt I needed my own 'castle,' so I built this thing [nōgakudō]. But I wonder what the younger generation will do." At the time I didn't understand the significance of what he had said. Hisami and my father, Shigeo Yoshida, had been friends since they were both students at Seishikan Junior High School, and my parents and four sisters and I took lessons at the nōgakudō. So at the time I thought it was common for Noh performers to have their own theaters and to hold regularly scheduled performances there.

During a televised interview Hisami once said, "The Noh stage that had been at my home ever since I was born burned down in the air raid on Fukuyama, and I felt I needed my own 'castle,' so I built this thing [nōgakudō]. But I wonder what the younger generation will do." At the time I didn't understand the significance of what he had said. Hisami and my father, Shigeo Yoshida, had been friends since they were both students at Seishikan Junior High School, and my parents and four sisters and I took lessons at the nōgakudō. So at the time I thought it was common for Noh performers to have their own theaters and to hold regularly scheduled performances there.

When I consider how hard it is to continue to stage high-quality performances in a small town like Fukuyama, inviting performers from the Kansai area and Tokyo, I realize what a great man Hisami was, and I wonder what sort of answer we can offer in reply to what he said back then.

But having "this thing" (the Noh stage) enabled us to raise our four children, Kinue, Teruhisa, Fumie and Norie, because they were raised in a home in which there was a Noh stage upstairs, because they appeared as kokata in performances that were continually being planned and because they had to practice shimai and Noh every day.

In September 1986, when Kinue, Teruhisa and Fumie were in the sixth, fifth and third grades, respectively, and Norie was in kindergarten, the four of them appeared as kokata in a regularly scheduled performance during which Tōsen was staged. I'm sure it was tough for the children to rehearse during the hot days of August, but I must tip my hat to Hisami for his patience and stamina in disciplining them to do so. Like his father Hisatarō, I suppose Hisami had the same passionate desire to "pass nōgaku down to posterity." On the day of the performance of Tosen, while helping Hisami put on his costume as shite, Tomitaro Wajima said, "I envy Hisami." Hisami, who was about to appear on stage with his four grandchildren, must have looked very happy indeed.

In September 1986, when Kinue, Teruhisa and Fumie were in the sixth, fifth and third grades, respectively, and Norie was in kindergarten, the four of them appeared as kokata in a regularly scheduled performance during which Tōsen was staged. I'm sure it was tough for the children to rehearse during the hot days of August, but I must tip my hat to Hisami for his patience and stamina in disciplining them to do so. Like his father Hisatarō, I suppose Hisami had the same passionate desire to "pass nōgaku down to posterity." On the day of the performance of Tosen, while helping Hisami put on his costume as shite, Tomitaro Wajima said, "I envy Hisami." Hisami, who was about to appear on stage with his four grandchildren, must have looked very happy indeed.

This year marks the seventh anniversary of Hisami's death. This fall Teruhisa will make his first appearance in Dōjōji in a memorial performance commemorating his grandfather. I would like to express my gratitude to Mr. Akiyo Tomoeda, Mr. Akio Shiotsu and others of the Kita school, the performers who will appear on stage with Teruhisa and the many others who have supported him since he went to Tokyo and ask for your continued guidance and encouragement. (translated by Nancy Ross)

№21 cover story (2010/04/15)

Receiving the Hir2022-07-18bu

Since 1957, when at the age of fifteen I became an apprentice of KITA Minoru, the 15th head of Kita-ryu, I have been exercising this art for more than fifty years. Fortunately, I was able to receive the Hiroshima Education Award of Heisei 21. Mr YOKOYAMA Haruaki, who lives in Hiroshima City and is a master of Ko-tsuzumi, was also awarded this time. This proves, I am sure, that Hiroshima Prefecture has come to evaluate the value of Noh-gaku in the field of education.

Since 1957, when at the age of fifteen I became an apprentice of KITA Minoru, the 15th head of Kita-ryu, I have been exercising this art for more than fifty years. Fortunately, I was able to receive the Hiroshima Education Award of Heisei 21. Mr YOKOYAMA Haruaki, who lives in Hiroshima City and is a master of Ko-tsuzumi, was also awarded this time. This proves, I am sure, that Hiroshima Prefecture has come to evaluate the value of Noh-gaku in the field of education.

Noh-gaku, having flourished as a ritual music for samurai during the Edo Era, but having rather declined just after the Meiji Restoration, revived under the support of the political and financial leaders. After the Second World War, however, the mainstream was the Western Culture and our Japanese traditional culture seldom appeared at school. Only recently the stream has been changing, as the Ministry of Education insists that the Japanese culture should be taught. That is why I received the award.

I had good opportunities to perform Noh in two Scandinavian countries in May, three European countries in December of last year. The people in Europe nicely appreciated our performances. I wish more and more teachers on the podium in Japan could appreciate Noh-gaku and guide the pupils to it. It is a matter of great urgent which has to be done by us. I sincerely ask all of you for your help. Thank you very much.